This is the third blogpost in the series about The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia. The book will be out in two months in January 2024. I am very excited about this and looking forward to receiving comments from the readers and reviewers.

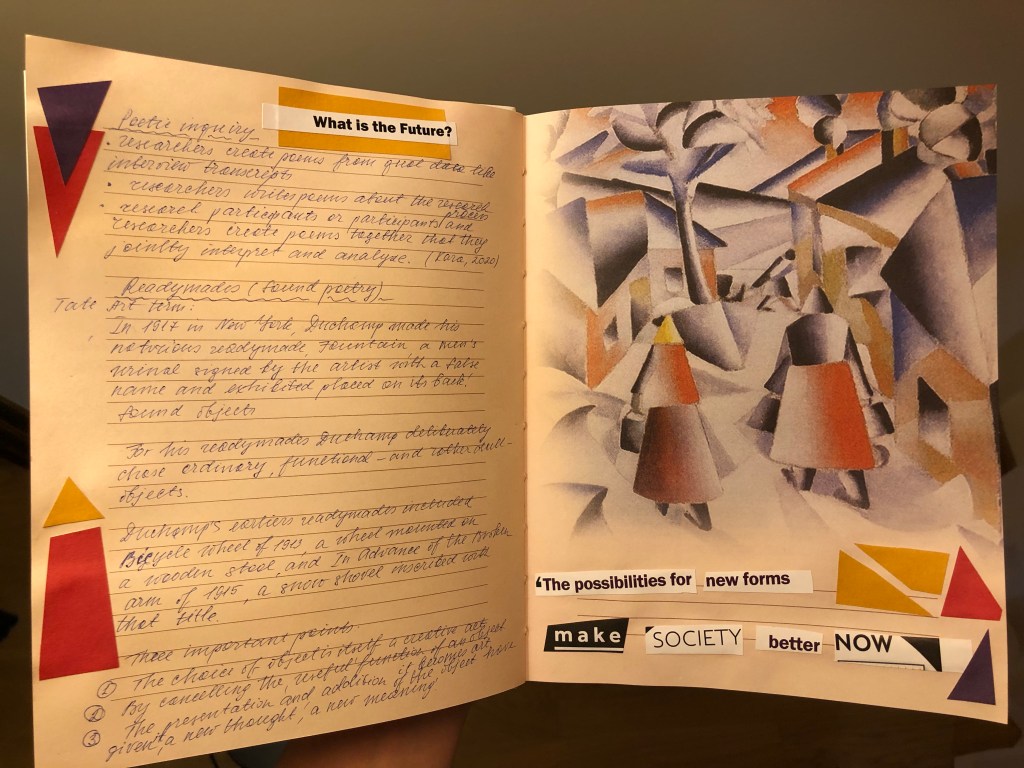

From its short description, you may learn that the book draws on the ethnographic study with elements of arts-based research. Earlier I wrote about how I integrated poetry in academic writing (read here). In this post, I would like to explain how I used illustrations to support the textual narrative and my overarching argument.

The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia includes about 30 black and white illustrations of three types.

First, I illustrate one of my arguments about the complexity of socio-spatial imaginaries with drawings of the industrial neighbourhoods and Russian society made by research participants with a black pen. I obtained these drawings with verbal explanations during interviews with workers and professionals. Drawings with explanations are multi-sensory data created by participants. That is why I view my participants as co-creators of unique data for this ethnographic study. These drawings are as important as interview narratives and other data. They visualise the feelings of residents of the industrial neighbourhoods to their places of residence and their subjective perceptions of inequality and whole Russian society.

Second, I use some ethnographic photographs taken during fieldwork in Moscow and Yekaterinburg cities. The photographs help to provide the reader with a sense of atmosphere in two locations studied. Some of them show the urban settings and infrastructure of the industrial neighbourhoods. Some others focus on practical activities of ordinary people, such as collective maintenance of deindustrialising areas and cultivating mini-gardens near social housing blocks. For illustrations, I selected those photographs that did not show particiapants’ faces to align with the ethical principles of anonymity. I also use a photograph of a massive May Day Demo in St. Petersburg by Pyotr Prinyov from the mid-2010s to explain better the restrictions for open protests in today’s Russia.

Finally, I crafted several graphic illustrations with the help of drawing skills that I learnt from artist Victoria Lomasko within our course ‘Avant-garde and arts-based methods in qualitative research’. With a black marker, I drew the portraits of some research participants, as well as workers of different ages, genders and ethnicities who I met in a post-industrial city. Moreover, I entitled the first part of the book ‘Theoretical sketches’ not only because ‘Poetical Sketches’ by William Blake inspired my writing. Synthesising a novel theory of urban life, this first part includes my graphic sketches visually explaining the conceptualisation of structure of feeling and everyday struggle.

In the book, I combine the textual register with the visual one to tell the story about the urban life of workers vividly and vibrantly. The idea of such a creative approach to academic writing is not (only) to entertain the reader but not to leave them indifferent.

If you are interested in writing a book review, you can request a free copy of The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia on the website of Manchester University Press (click here). If you can, please purchase the book via your University or local library to make it available to a wider community of readers (click here).