This is the second part of the blogpost with my response to the reviewers who engaged with ‘The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia’ to be released in paperback in January 2026. In this part, I would like to discuss some comments on my book by Paupolina Gundarina and Mitja Stefancic.

In her essay ‘“Soviet in post-Soviet” in Alexandrina Vanke’s book The Urban Life of Workers in Post-Soviet Russia: Engaging in Everyday Struggle’, published in Russian on the Syg.ma platform, Paupolina Gundarina provides a very sensitive and careful reading of my book. She views my research as ‘an ambitious and creative ethnographic description of workers’ communities, which opens up new dimensions of (the working) class, creativity, imagination and phenomenology of home’.

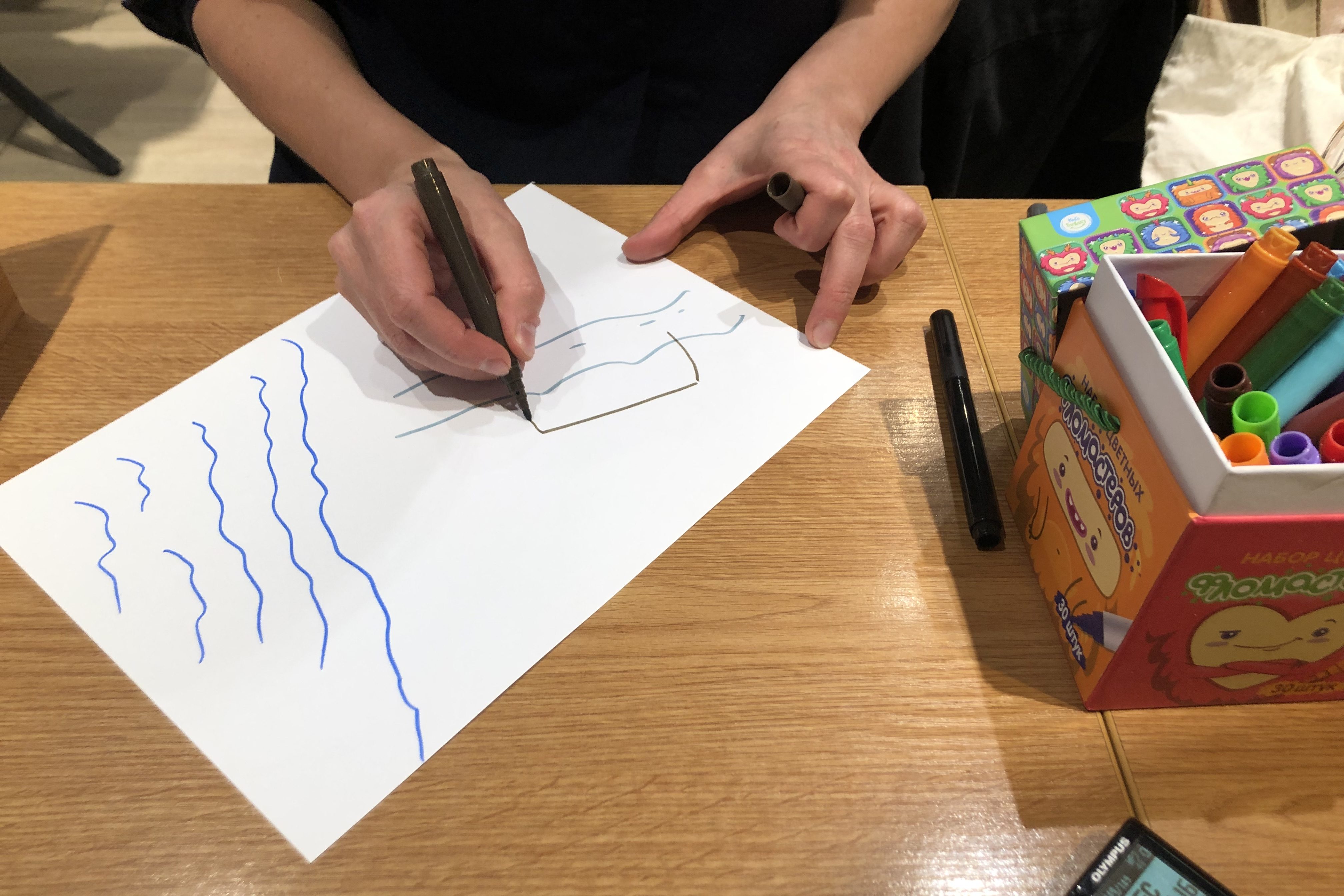

Gundarina finds my methodology, drawing on multi-sited ethnography, innovative and creative. She especially highlights the participatory nature of my study, when I invited research participants to draw their neighbourhood and society, which allowed me to grasp their ‘affective experience[s]’. As the reviewer stresses, this methodology opens up new opportunities for the debate about emotions regarding deindustrialisation and their relationships with the Soviet legacy and ‘the issues of morality, trauma, nostalgia, loss and adaptation’.

‘[T]his is an ambitious and creative ethnographic description of workers’ communities, which opens up new dimensions of (the working) class, creativity, imagination and phenomenology of home.’ Paupolina Gundarina

Continuing this discussion, I would place my methodology within two developing strands. On the one hand, it is situated within the range of ethnographies paying particular attention to sensory-ness, affect and the imaginary. On the other hand, it develops creative, visual and arts-based methods. In my forthcoming article, I call this approach ‘avant-garde methodology’ which generates alternative interpretations of class experiences.

Gundarina finds my revision of class struggle, which I reconsider within the everyday realm, as an important contribution to the Marxist debate on class and resistance. As she writes, ‘Vanke’s book challenges economic determinism showing that the working class in post-Soviet Russia is defined through everyday practices, spatial belonging and grassroots resistance, not just through employment status’. She correctly reads my argument about the formation of classes in Russia’s major cities as ‘a constant, contradictory process, which is influenced by both the Soviet legacy and neoliberal change’.

As Gundarina discusses further the ethnographic examples from my book, ordinary people continue to implement Soviet practices in deindustrialising urban spaces. But indeed, in the neoliberal context, these practices gain new meanings, allowing residents of industrial districts to cultivate class feelings and attachment to place, for example, through collective maintenance and decoration of the depleting infrastructure remaining from the Soviet era. According to my approach, these practical activities fall under the category of everyday struggle.

I especially enjoy that the reviewer included her Russian translation of some research participants’ quotes from the book and provided her example of the controversial local debates around a DIY swan created by a local resident of Barnaul, a Western Siberian city of Russia, and put in a public place.

The book review by Mitja Stefancic, published in the 50th Anniversary Issue of Network, magazine by the British Sociological Association, continues to discuss my book in light of the class debate. As he writes, ‘One of the main achievements of the book lies in its successful attempt to re-discuss the concept of class’. Stefancic stresses the importance of my research as it ‘shows how class in Russia means something different when compared, for example, to Western societies’. This conversation about classes continued in an interview with me by Stefancic published in Serbian, English and Italian. I am very grateful for this opportunity to discuss my research outputs beyond academia.

‘One of the main achievements of the book lies in its successful attempt to re-discuss the concept of class. In fact, on a theoretical level, Vanke effectively shows how class in Russia means something different when compared, for example, to Western societies.’ Mitja Stefancic

Indeed, unlike Western countries with stable social structures, Russia has experienced political upheavals and socio-economic reconfigurations of social groups during the 1990s, which influenced how people perceive classes and inequalities. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a new social structure is being formed in contemporary Russia framed by the neoliberal neo-authoritarian order of power.

My field research conducted before 2022 revealed polarisation in the social structure with a split between the poor and the rich, as I argue in the book and in my article on lay perceptions of inequality (read its summary on Everyday Society). However, sociologically it is interesting to understand how the Russia-Ukraine war will reconfigure the social structure and redistribute social wealth and capitals between particular segments of Russian society.

Stefancic concludes that my book helps to understand better Russian society itself and will be of interest to those who are focusing on how working classes around the globe overcome life difficulties while being excluded from big politics. In light of the global shift of the political mainstream to the right, as discussed in the August issue of Global Dialogue, my approach to everyday struggle in restrictive conditions has the potential to be transferred to other contexts.