I got a wonderful news from Manchester University Press about The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia. It will be out in paperback in January 2026. This means that the book will be available at a more affordable price soon. As recent reviews show, since its first edition in January 2024, the book remains highly relevant, widening discussion about the working classes, deindustrialisation, inequalities and everyday struggles.

In one of the previous blog posts, I replied to the first book reviews by sociologists Claudio Morrison and Christopher Altamura. In this blog post, I would like to continue this conversation about class with other commentators on the book, which appeared in the first half of 2025. I will engage with them in the chronological order in which their reviews were published.

In Challenging Stereotypes of Post-Soviet Russian Workers (CEU Review of Books), Victoria Kobzeva from the University of Birmingham provides critical comments on my theoretical framework, researcher positionality and interpretations of workers’ acts of everyday resistance. On the one hand, Kobzeva writes that the book introduces ‘a dozen concepts’ that are pivotal for my further ethnographic interpretations. On the other hand, she claims that my theoretical contribution to social theory, especially to Pierre Bourdieu’s approach of habitus, ‘feels limited’ despite rich empirical data.

‘Vanke’s book is an example of immersive, prolonged ethnography enriched by creative methodologies and a deep engagement with the lived experiences of Russia’s urban working class.’ Viktoria Kobzeva

When an author meets such criticism, it leads to reflection on what theoretical contribution means and how to increase it in future publications. Below, I would like to address this point of criticism.

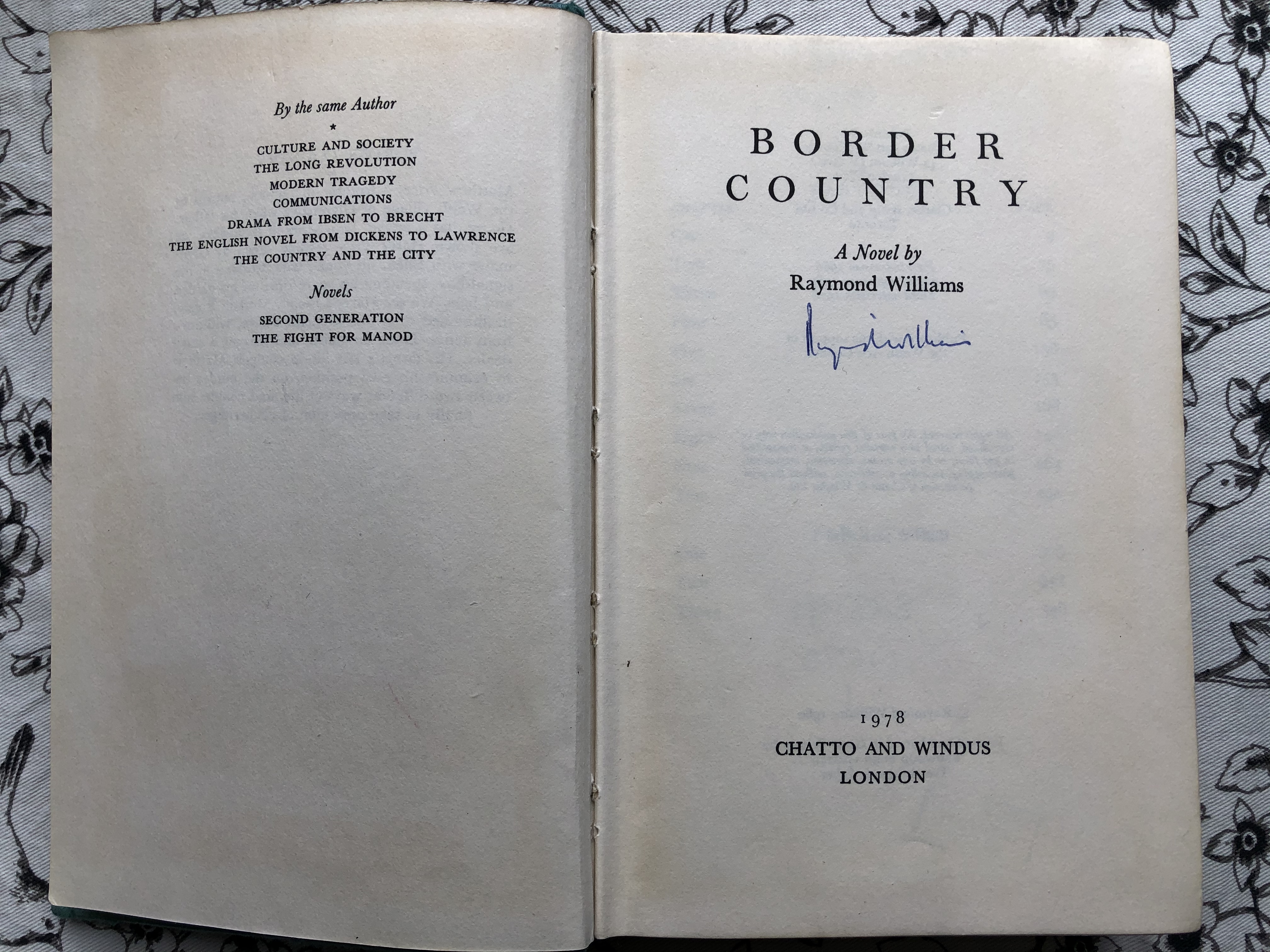

The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia develops some theoretical concepts further. The book engages with ‘structure of feeling’, introduced by Raymond Williams, which I re-conceptualise as an affective principle regulating senses, imaginaries and practical activities within socio-material infrastructures, drawing on multi-sited ethnography in post-socialist deindustrialising contexts. The book also conceptualises everyday struggle, by which I mean a set of multiple counter-hegemonic acts, micro-practices and activities performed by workers and ordinary people in everyday life. I agree with Kobzeva that everyday struggle needs to be theorised further, as this concept differs from mundane resistance, introduced by James Scott, even though it encompasses resistance. However, I see working with everyday struggle as my contribution to theories of struggle and protest, which mainly focus on overt protests and social movements in Western liberal democracies.

Next, in the book, I map these and other concepts, visualising relationships between them in two theoretical sketches, and synthesise them into a theory of urban life and everyday struggle. I am still thinking about what this theory could be called: multi-sensory, affective or imaginative? The idea of everyday struggle embedded in life leaves room for reconsidering the concept of habitus, through re-viewing it as a set of dispositions of resistance and counter-actions.

The suggested framework adds affective, sensory and imaginative dimensions to the understanding of class and struggle that, as my ethnography shows, goes beyond coping and resistance. This framework opens up an opportunity to think about social change at the micro-level, enacted through enduring dispositions of co-creation and re-shaping. In the book, I also deal with the concept of spatialised gender habitus, or a gendered sense of place. I agree with the reviewer that it needs to be developed further, probably in future publications.

In the book, I do not introduce new concepts. What I do is theorise and synthesise existing concepts based on extensive multi-sited ethnography in Russia’s post-industrial cities. If such a framework contributes to the de-stigmatisation of low-resourced groups in post-socialist settings and can potentially be discussed and adopted (with adjustments) in other ‘local’ contexts, then my goal as an author will have been met.

However, there is still an open question about whether everyday struggle is exclusively working-class, and whether it allows class consciousness, as was asked in the review by Morrison. My continuing ethnography shows that not only working-class people engage in everyday struggle, but that it is still informed by how people sense inequality locally, imagine social justice in society and view the global future.

‘The Urban Life of Workers in Post-Soviet Russia: Engaging in Everyday Struggle (published by Manchester University Press in 2024) by Alexandrina Vanke is an innovative and textured engagement with the world of the working class in the post-industrial cities of Russia.’ Arpita Rachel Abraham

The book review by Arpita Rachel Abraham, an Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements in Bengaluru, published on the Doing Sociology platform, continues the discussion about class consciousness, urban change, critical sociological theory and ethnography from the perspective of the impact of ‘global political developments’ and ‘Russia’s aggression on Ukraine’ on the working classes and ordinary people. Abraham stresses that my book advances the theory of the everyday, which is often lacking a political dimension. She points out that my research shows that the political is part of everyday life in neoliberal neo-authoritarian contexts. In this sense, my book bridges two separate areas: everyday life studies and social movement studies.

Praising ‘an impressive assemblage of textual, visual and performative elements’ in the book, Abraham raises a critical question about the one-dimensionality and repetitiveness of the argument regarding workers’ active engagement in everyday struggle. I would like to explain that the idea behind writing this book was to make this core argument part of academic storytelling, using it as the key element that would sew all chapters together like a needle. In the next book, I will probably experiment with integrating more authorial ideas and less polished arguments, which I will present not as analytically justified statements but as diverse interpretations, provoking new directions, debates and conversations on the subject matter.

I am grateful to both Victoria Kobzeva and Arpita Rachel Abraham for their interest in my book and for writing reviews that widen the discussion about the issues considered in The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia.

In the second part of this blog post, I will reflect on the comments from the reviews of my book by Paupolina Gundarin and Mitja Stefancic.

To be continued…