On the background of hot debates about Russia, I got the final version of the front cover of my forthcoming book to be released just in four months, on 16 January 2024. Drawing on multi-sited ethnography, The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia: Engaging in everyday struggle creatively explores the lived experiences of working-class and wider deindustrialising communities in the cities of Moscow and Yekaterinburg, and beyond.

In this blog post, I would like to discuss the visual aesthetics of the book mainly focusing on its front cover image. It contains some elements of the poster The 1st of May. The All-Russian subbotnik created by graphic artist Dmitrii Moor (Orlov) in 1920. A brief overview of his life will help to explain better his artistic approach. Moor was born in the family of an engineer in Novocherkassk in 1883. After moving to Moscow in 1989, he got a vocational education and participated in the Revolution of 1905. This experience made him realise that he should present the voice of working-class people through the artistic means (see Kozlov, 1949). Moor did not have a formal art education, but inside the country, he was considered to be a People’s Artist, while his art was called ‘proletarian art’. To the international audience, Moor may be known for his avant-garde posters and political caricatures.

In The 1st of May, Moor depicted working-class people on May Day engaged in building and maintaining not only the industrial urban infrastructure but also the fabric of everyday life. This visual representation of workers as acting aligns with my main argument about workers’ engagement in the creative forms of mundane resistance which, as I explain in the book, falls under the category of everyday struggle.

For the greater effect, Moor used a combination of black, beige and red colours which characterise his graphic art style. The message of his image is clear and concise. The poster realistically shows the urban life of workers and emphasises their class consciousness: the themes my book explores in detail. In the background, one can see the industrial urban landscape with the train, some factories and power lines telling us about industrialisation and electrification in the early-Soviet era. There are two inscriptions on the top reading ‘Russian Socialist Federation of the Soviet Republic’ and ‘Workers Of All Countries Unite!’ (see also). There is the capitalised poster title at the bottom.

In his poster, Moor glorifies subbotnik – the word derived from subbota meaning Saturday – which is a voluntary collective activity of cleaning and maintaining the urban infrastructure or the workplace emerged right after the October Revolution. Subbotniks usually took place on days off around Vladimir Lenin’s birthday on 22 April. Very quickly from a volunteer activity they turned to be free labour of Soviet people. Emerged in the early-Soviet era, subbotnik as a practice survived the dissolution of the USSR and has gained new meanings in contemporary Russia. In Chapter 7, I analyse top-down and grassroots subbotniks organised in one industrial neighbourhood where I did ethnography.

I especially enjoy that Moor’s image shows not only the strength of working-class men but also working-class women. Chapter 3 of my book considers power relations in deindsutrialising communities mediated by the intersections of class, gender, age and ethnicity/race.

Before I started writing the book, I thought that Moor’s image may be good for the front cover. To obtain this image in high resolution, I went to the Lenin Library in Moscow, ordered it from the archive and photographed it. As far as another poster was glued on the backside of The 1st May from the library’s collection, some of the bleedthrough from it are visible in my photo.

At the stage of book production, I suggested the publisher to use my photo of Moor’s poster for the front cover. It was so exciting to see that Manchester University Press put this image on the front cover of their Autumn/ Winter 2023 catalogue.

The MUP designer created several front covers for my book differed by the title fonts and colour shades. I am very glad that in its final version, Moor’s avant-garde image from The 1st of May aesthetically resonates with the title font of The urban life of workers in post-Soviet Russia.

You can find the book details and recommend it to your library on the website of Manchester University Press. The book is also available to pre-order via the following booksellers.

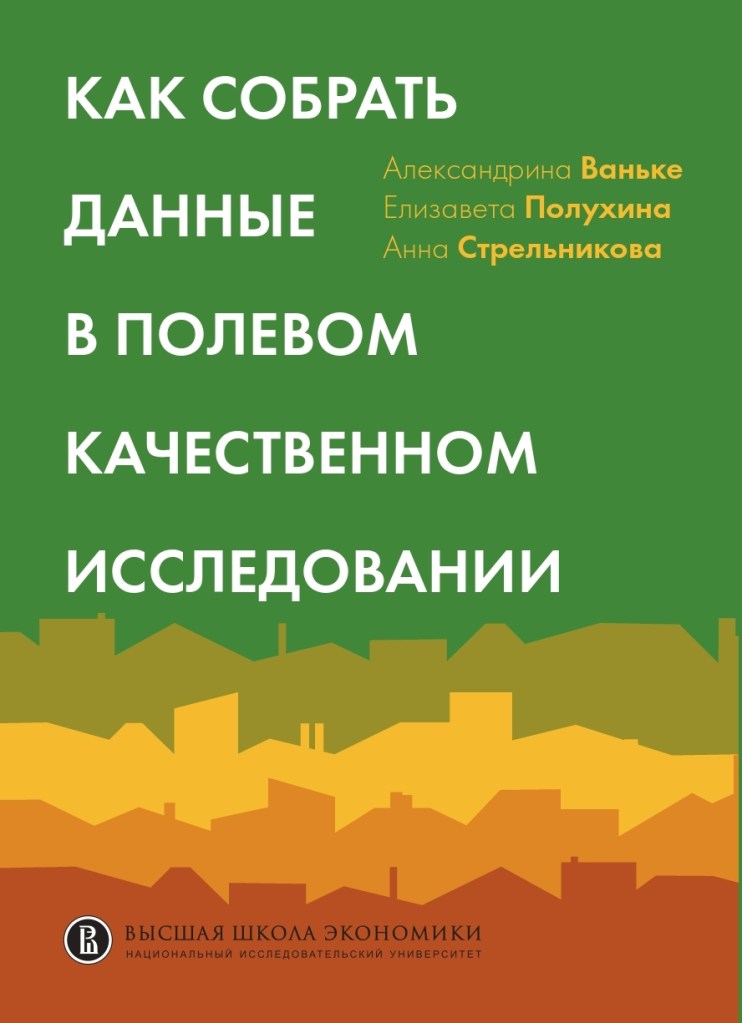

Наше учебное пособие в соавторстве с Елизаветой Полухиной и Анной Стрельниковой

Наше учебное пособие в соавторстве с Елизаветой Полухиной и Анной Стрельниковой

Аннотация. Углубление социального неравенства, которое автор связывает с глобальным распространением неолиберализма, усложняет систему властных отношений между мужскими телами и сексуальностями и ведет к дифференциации типов маскулинности. На материале 43 биографических интервью переосмысляются властные отношения внутри двух социально-профессиональных сред — так называемых синих и белых воротничков. Автор приходит к выводу, что через регулирование телесности сфера труда управляет эмоциональными отношениями и, как следствие, сексуальной жизнью мужчин из обеих групп. Наряду с этим режимы производственного и офисного труда генерируют разные логики управления мужской телесностью, которые воспроизводятся в приватной сфере и используются для создания мужской субъективности.

Аннотация. Углубление социального неравенства, которое автор связывает с глобальным распространением неолиберализма, усложняет систему властных отношений между мужскими телами и сексуальностями и ведет к дифференциации типов маскулинности. На материале 43 биографических интервью переосмысляются властные отношения внутри двух социально-профессиональных сред — так называемых синих и белых воротничков. Автор приходит к выводу, что через регулирование телесности сфера труда управляет эмоциональными отношениями и, как следствие, сексуальной жизнью мужчин из обеих групп. Наряду с этим режимы производственного и офисного труда генерируют разные логики управления мужской телесностью, которые воспроизводятся в приватной сфере и используются для создания мужской субъективности. Аннотация. В статье рассматриваются территориальные идентичности, сформировавшиеся вокруг советских предприятий: завода имени И. А. Лихачева (ЗИЛ) в Москве и Уральского завода тяжелого машиностроения (Уралмаш) в Екатеринбурге. На примере двух кейсов авторы отвечают на вопрос о том, как создается территориальная идентичность индустриальных районов в постсоветской России. Авторы анализируют культурные практики в двух индустриальных районах и показывают, какой вклад в изменение их территориальных идентичностей вносят культурные акторы: представители творческих профессий и культурной среды, то есть научные работники, художники, архитекторы, фотографы, преподаватели высших учебных заведений, работники музеев, культурные и городские активисты. Исследование обнаруживает увеличение социального неравенства между резидентами индустриальных районов: рабочими и представителями других социальных групп. На фоне неолиберальной политики новые социальные акторы приходят в индустриальные районы, изменяя конфигурацию их социального состава. Оба кейса – территории вокруг завода имени И. А. Лихачёва и Уралмашзавода – демонстрируют наслоение разных типов идентичности и ассоциирующихся с ними культур рабочего и среднего классов. Так, в случае индустриальных районов мы можем говорить о множественной территориальной идентичности, которая выражается в том, что коренные жители и новые культурные акторы применяют классово дифференцированные «советские» и «постсоветские» культурные практики, воспроизводят «старые» и «новые» стили жизни.

Аннотация. В статье рассматриваются территориальные идентичности, сформировавшиеся вокруг советских предприятий: завода имени И. А. Лихачева (ЗИЛ) в Москве и Уральского завода тяжелого машиностроения (Уралмаш) в Екатеринбурге. На примере двух кейсов авторы отвечают на вопрос о том, как создается территориальная идентичность индустриальных районов в постсоветской России. Авторы анализируют культурные практики в двух индустриальных районах и показывают, какой вклад в изменение их территориальных идентичностей вносят культурные акторы: представители творческих профессий и культурной среды, то есть научные работники, художники, архитекторы, фотографы, преподаватели высших учебных заведений, работники музеев, культурные и городские активисты. Исследование обнаруживает увеличение социального неравенства между резидентами индустриальных районов: рабочими и представителями других социальных групп. На фоне неолиберальной политики новые социальные акторы приходят в индустриальные районы, изменяя конфигурацию их социального состава. Оба кейса – территории вокруг завода имени И. А. Лихачёва и Уралмашзавода – демонстрируют наслоение разных типов идентичности и ассоциирующихся с ними культур рабочего и среднего классов. Так, в случае индустриальных районов мы можем говорить о множественной территориальной идентичности, которая выражается в том, что коренные жители и новые культурные акторы применяют классово дифференцированные «советские» и «постсоветские» культурные практики, воспроизводят «старые» и «новые» стили жизни. The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives with my entry Fear of War has finally been released.

The SAGE Encyclopedia of War: Social Science Perspectives with my entry Fear of War has finally been released.